The Birth of the Dutch City Block

Weavers’ Blocks in the Golden Age

Abstract

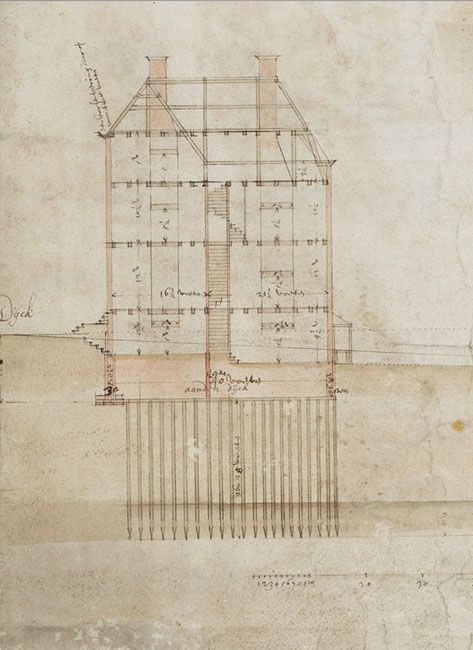

Dutch housing culture has its origins in the urban terraced houses in which people lived and worked for centuries, in all kinds of configurations. 1 The individual dwelling remained the determining unit of urban development until industrialization took off in the nineteenth century. However, even in the seventeenth century, people were thinking and designing on a larger scale; of this, the urban extension of the Amsterdam canal area is the best-known exponent. But while this extension plan concerned an entire district, in the end it was yet again the terraced house, in this case the chic canal-side house, that was the development unit. As a result, the character of the city block remained secondary, with the urban design dependant on individual owners.2 Much less known but all the more interesting are a number of projects from the same period that were actually based on the entire city block as a development and design unit. In quick succession, various architects in different cities took on the experiment to create designs for city blocks that combined living and working for a specific target group, namely weavers and their families.

This article will compare three of these weavers’ blocks and join the architects in their search for the added value of the city block as a design unit. What advantages did they see? What design choices did they make on the basis of perceived advantages? Did the combination of living and working in these artisan dwellings influence the design, and which criteria were decisive? What could the designers refer to in their façade designs given the fact that the entire city block was the architectural unit? And finally, with regard to flexibility: How did they guarantee that they would be able to find tenants, should the weavers stay away? These are questions that, if you look at current discussions about urban living and working blocks, have lost none of their topicality.