Editorial

Abstract

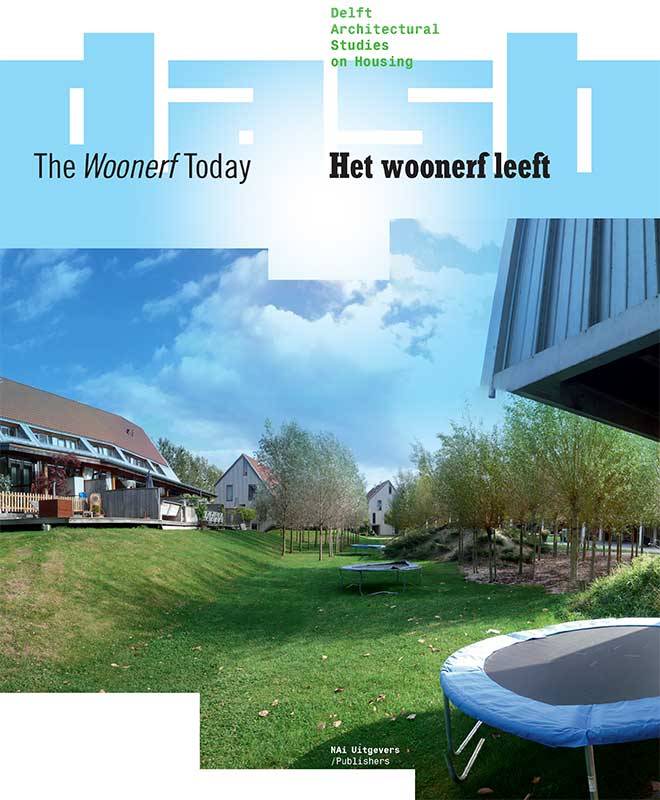

Exactly 20 years ago, Rem Koolhaas predicted the rediscovery of the Tanthof, a woonerf or home zone in Delft, in his infamous diatribe against the era’s neomodernism, How Modern Is Dutch Architecture? The prediction was no more than an ironic, perhaps even sarcastic interjection in his Philippic, aimed at riling young colleagues such as Mecanoo or DKV. Although Koolhaas’s prophecy has not come true (yet), the ‘cauliflower neighbourhoods’, the derogatory label now attached to the suburban developments from the 1970s and ’80s, are undeniably due a reassessment. The fact that the neighbourhoods and houses are falling into disrepair and the composition of the population is changing, is putting them back on the radar of institutional managers and policymakers. The first few studies and surveys have already been carried out, but the fate of this collection of mass small-scale developments and planned everyday happiness has yet to be decided.

In professional circles it is certainly the done thing to dismiss the architecture and planning from this era as one big mistake. Some people are even calling for a large-scale reconstruction effort, similar to the one targeting post-war neighbourhoods. But at the same time there are signs of a nostalgic revival among the generation that grew up with the aesthetics of cosiness, sunken seating areas, railway sleepers and washed gravel stones in the garden. The 2004 NAI exhibition and publication The Critical Seventies, in which the socalled ‘new twee’ was quite prominent, was an early expression of this revival.